The war has led to the closure of Ukrainian Black Sea ports. Sanctions are starting to block Russian grain trade shipments. Large war risk premiums are deterring bulk carriers from trading out of the Black Sea. On face value, this appears adverse for dry bulk shipping with a potential significant loss of trade. These will be hard to replace from alternative producers. Soaring grain prices looks set to further erode grain demand.

However, there are some positives when we dig a little deeper into patterns of grain trade out of the Black Sea. We also look at other implications from the war already impacting fertiliser and vegetable oil trade.

The Position Before the Outbreak of War

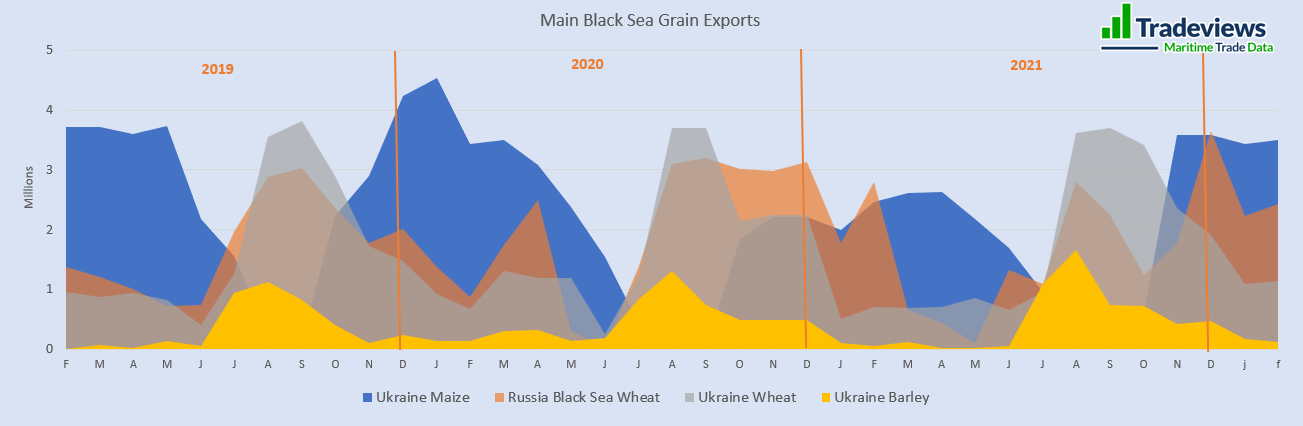

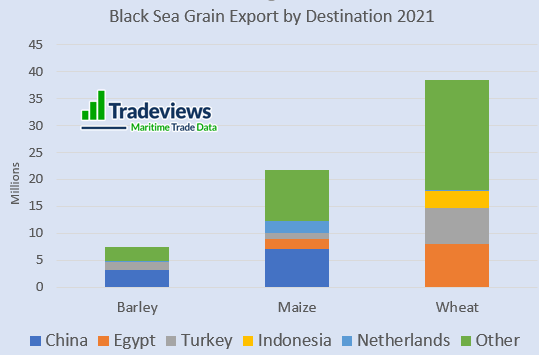

The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) released its February monthly grain outlook on the 9th of February ahead of the outbreak of war. Global wheat exports for the 2021/22 season were estimated at just under 207 Mmt of which Russia accounted for 35 Mmt (16.9%) and Ukraine for 24 Mmt (11.6%). Global maize export trade for 2021/22 was estimated at just under 204 Mmt of which Russia accounted for 4.5 Mmt (2.2%) and Ukraine for 33.5 Mmt (16.4%). As for barley, the USDA estimated global export trade in 2021/22 at just over 34 Mmt of which Russia accounted for 4.5 Mmt (13.2%) and Ukraine for 6 Mmt (17.6%).

After the Outbreak of War

The USDA updated its grain outlook on the 9th of March and trimmed exports out of Russia and Ukraine over the remainder of the 2021/22 season. Wheat exports out of Russia were cut by 3 Mmt while exports out of Ukraine were cut 4 Mmt, and only partly offset by rises in shipments out of Australia (up 2 Mmt) and India (up 1.5 Mmt). Russia’s more modest maize exports were held at 4.5 Mmt while Ukraine’s maize exports were slashed by 6 Mmt, partly offset by a 1.9 Mmt markup in U.S. exports. As for barley exports, the Russian export assessment was unchanged while the Ukrainian estimate was reduced by a modest 0.2 Mmt as most of the current season’s export shipments were made earlier in the season.

The more serious worries over trade volumes will come in the 2022/23 season which for both Russia and Ukraine start in July in the case of wheat and barley and in October for maize. Ukraine’s wheat exports typically peak between August and October and between July and October in the case of barley and are both predicated on an earlier sowing season which is due to start in the next few weeks. With war raging, a mass exodus of the population and working-aged men downing tools and taking up arms, the outlook for next season’s Ukrainian grain production looks bleak at best. While Russian grain production will be less impacted, its exports are set to be squeezed by the severe tightening of sanctions.

The Global Picture

Soaring grain prices are already driving up food price inflation. Whilst more affluent counties are better able to absorb rising costs and to compensate by changes in food selection, poorer countries face more severe problems. The U.N.’s World Food Programme is already warning of rising food prices and global hunger following on from a pandemic that has pulled millions more into poverty. As we discuss shortly, fertiliser price inflation and disruption to key supplies is compounding the difficulties faced by global grain producers to meet the challenge of boosting grain supply to compensate for a fall off in Ukrainian and Russian shipments.

Changes to the Pattern of Grain Trade

Much of Black Sea grain trade is shipped over short distance to two key markets, namely Egypt and Turkey. Both counties will be forced to look further afield for alternative supplies creating more bulk carrier demand. Australia is expected to boost its exports which are already seeing lengthening export voyages following China’s ban on importing Australian barley. There are some concerns over the extent to which Australia can boost its grain trade exports through its port grain terminals given lorry driver shortages in the country. Higher wheat exports out of India are likely to go to more immediate neighbours such as Bangladesh and Sri Lanka which may have a net negative effect on bulk carrier demand.

Fertiliser Trade

There are three key components in fertilisers that boost plant growth and crop yields, namely potassium, phosphorous and nitrogen. Nitrogenous fertiliser production is heavily dependent on natural gas via the manufacture of urea and ammonium nitrate. Inflated natural gas prices have been further boosted by the onset of the war in Ukraine to the point that some fertiliser manufacturers have ceased production as being uneconomic. Russia is an important supplier of nitrogenous fertilisers particularly to countries in eastern Europe and central Asia.

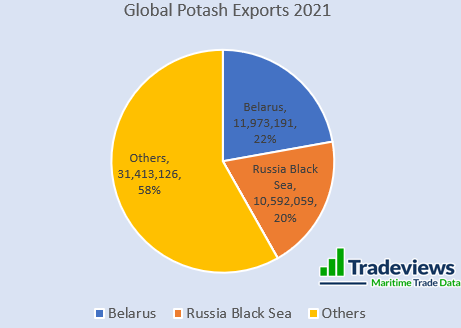

Potash is the primary source of potassium in fertilizer production. Potash is a water-soluble compound of potassium and the world’s major deposits were formed from the evaporation of ancient seas and lakes leaving layers of potash salts. The three leading potash exporters are Canada, Russia, and Belarus (Russia’s partner in the war in Ukraine). The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that Russia and Belarus accounted for 37% of global potash mine production in 2021. Sanctions on exports from these two nations will only add to pressure on fertiliser prices and supply. Lack of fertiliser supply and unaffordable prices looks set to reduce crop yields and lead to grain shortages with poorer nations again hardest hit.

Oilseed Trade

The USDA estimates that Ukraine accounts for 48% of global sunflower seed oil exports with Russia accounting for a further 29%. Oil crush extraction facilities at Ukrainian ports have already ceased operation. The UN’s FAO estimate in its latest update said that around half of Ukrainian and Russian exports in the 2021/22 season were shipped out between last October and February leaving a balance of 3.3 and 1.9 Mmt due to be exported over the remaining seven months of the season that are now set to disappear. Key importers of Ukrainian and Russian sunflower seed oil include India, the E.U. and China with smaller volumes going to Iran and Turkey.

Russia and Ukraine also account for around one-fifth of global rapeseed exports just over 15% of rapeseed oil exports. As the USDA notes. Finding alternative vegetable oils will be a challenge in a market that has been facing tight supplies even before the war in Ukraine.

Conclusion

The war in Ukraine has disrupted grain trade, fertiliser and oilseed supply, boosted grain prices, driven up food price inflation and looks set to constrain grain demand and inflict hunger on the poorest nations already reeling from the impact of the global pandemic. While there is the prospect of some increases in longer-haul grain shipments, it is hard to avoid concluding that the war will have a negative impact on dry bulk shipping.