This year has seen a string of disasters around the globe involving wildfires, drought and flooding. These events have driven environmental concerns up the political ladder and made coal Public Enemy No. 1 for environmental campaigners. With economies of scale reducing the costs of renewable energy, many argue that the days of burning coal appear numbered. Yet international coal trade appears very healthy given the recent surge in coal prices. What is going on?

Rising Prices

The benchmark landed price of imported thermal coal in Rotterdam averaged around $50/mt in 2020. It had pushed over $170/mt last week. The rise in metallurgical coal prices has been little short of astonishing. The landed price of imported premium coking coal in China averaged around $145/mt in 2020. Last week, it pushed up over $570/mt. This was despite recent Chinese government curbs on domestic steel production. These curbs have already led to a sharp drop in imported iron ore prices.

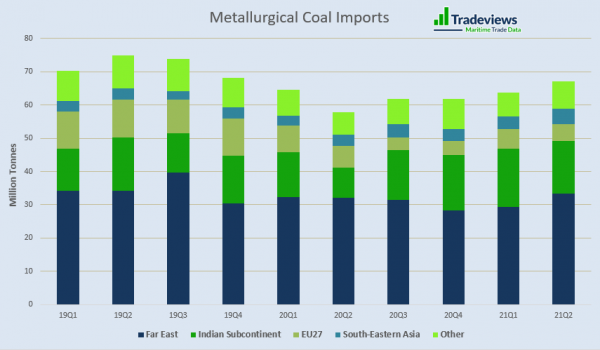

There are multiple factors at play in driving prices for international coal trade higher. International trade in coal has been disrupted and restructured by China’s import ban on Australian coal. This dispute is set to continue after the recent announcement of the AUKUS strategic defence pact between Australia, the U.S., and the U.K. After shunning Australian coal, China has been forced to look further afield for limited alternative sources of supply. Metallurgical coal supply was already tight due to several overseas mine closures.

Non-seaborne trade

To make matters worse, truck driver fears of Covid-19 have reduced Mongolian overland shipments of metallurgical coal to a trickle. This is because of concern over Covid-19 cases among truck drivers. The need to haul coal over longer distances has added to dry bulk carrier demand. Heavy ship congestion at Chinese ports and Covid-19 related inefficiencies in ship operations have a combined impact. The result is that the Baltic Dry Index has hit a twelve-year high, adding to landed commodity prices.

A key factor in driving up thermal coal prices has been record-high natural gas prices. This has made coal burn in power generation more competitive as well as providing a price pull. Constraints on thermal coal production have added to price pressure. Heavy rainfall in Indonesia during the first half of this year disrupted coal supply, including lower-grade lignite shipments to China. There have also been coal supply bottlenecks in South Africa and Russia.

Future Trade

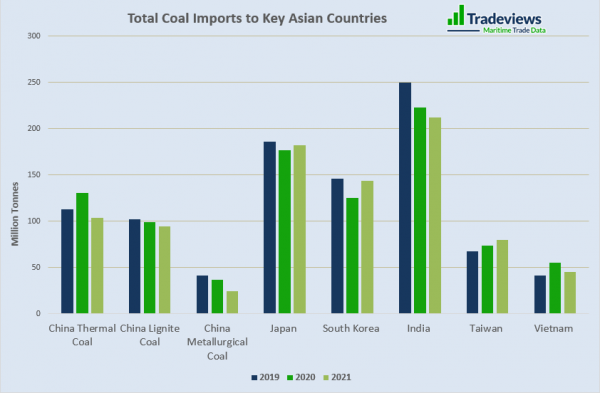

As for future coal trade, import demand will be increasingly Asia centric. Europe has already seen a notable decline in coal imports, which is set to continue. Austria and Belgium have ended thermal coal burning for power generation. Denmark, Finland, France, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain, Sweden, and the U.K. have all announced plans to end coal use in power plants. Albeit, over varying time spans. Other countries more reliant on coal and with domestic coal and lignite production, such as Germany, Poland, and the Czech Republic, are finding it harder to wean themselves off. However, the direction of travel is the same. Those committed to ongoing coal use are the Atlantic/Mediterranean basin, Brazil, Morocco and Turkey. Israel, however, is converting coal-fired power plants to gas.

Key Importers

The world’s largest coal importers are China and India. They are also the world’s most populated countries. Both China and India are heavily dependent on domestically supplied coal-fired power generation. Both governments have long-term policies to displace coal imports by boosting domestic output. However, this is proving difficult in the short term as power demand surged back as both economies reopened. Mine safety checks and fresh Covid-19 cases has lead to mandatory quarantining of coal truck drivers in North China. This has impacted Chinese domestic supply.

The Indian government has recently issued a directive to utilities to import more coal to cover shrinking stockpiles and to ensure that power demand is met. The problem for electricity generating utilities is that they struggle to pass on the current high price of spot coal. There is also the issues of high spot freight costs to customers given government electricity price controls.

Both Japan and South Korea have large fleets of coal-fired power plants heavily dependent on imported coal. Despite energy ministries’ long term plans to reduce coal dependency, significantly curtailing imports is unlikely over the next few years. Indeed, South Korea has plans to add new coal-fired units. Elsewhere in Asia, Taiwan is looking to reduce its coal dependency partly through conversions to gas usage. Vietnam’s coal imports have leapt in recent years. However, strict government enforced Covid-19 related lockdowns have held down imports this year.

Decarbonising Steel Production

Although individual country’s energy policies shape thermal coal imports, blast furnace steel production is tightly linked to metallurgical coal imports. Mainly scrap-based electric arc furnace steel production offers an alternative to using metallurgical coal. Rising electricity prices and the availability of scrap are a constraint on EAF output growth. China produces just over half of global crude steel production. China has plans to boost EAF’s share of domestic output. This is on the back of anticipated steady growth in the domestic supply of scrap. As noted earlier, the Chinese government is currently in the process of enforcing steel production cuts as it seeks to restrict crude steel output growth to 2020 levels.

There are no quick fixes for the decarbonization of steelmaking. Sweden-based SSAB has developed its HYBRIT project which produces sponge iron using renewable hydrogen gas to reduce iron ore thus avoiding the use of coal and coke. The company supplied its first fossil-free steel to Volvo last month. While the project shows that it is possible to produce green steel, the conversion of blast furnaces around the globe remains a daunting task. Moving away from metallurgical coal use will be a slow and very gradual process.

Summary

While it is easy to demonize coal, it is proving a lot harder for many countries to live without it. The long-term outlook is surely for a slow decline in coal usage and international coal trade. However, coal has been much in demand this year. Repeated demand is possible. Particularly if key coal dependant countries, like China and India, see unexpected disruption in domestic energy markets.