Tata Steel is in a standoff with the Labour Party and unions over the future of the country’s steel industry.

We look at:

- Tata’s plans for UK steel

- The high stakes poker game in play

- The contrast with Tata’s plans elsewhere in Europe

- What are other UK steelmakers doing?

- An overall perspective on the UK steel market

- Brexit – the elephant in the room

- Could scrap-based steel production work for the UK?

- How will all this play out?

Tata’s plans for UK steel

Tata has shut down its coke ovens and plans to close its two remaining blast furnaces at its Port Talbot site this year. One will be by the end of June and the other by the end of September. The company plans to build a new single three million tonnes/year scrap-based electric arc furnace (EAF). While construction is taking place, Tata will import steel for further processing from its Dutch and Indian operations plus from third parties. The plan was approval from the current Conservative government along with a grant of up to 500 million pounds.

The high stakes poker game in play

Tata has rejected the Labour party’s plea to keep one blast furnace running until the end of the decade. They say the future of steelmaking at Port Talbot would be placed at “significant risk” should the government grant be withdrawn. The Labour party, which is looking likely to form the next government, has pledged to invest 3 billion pounds in decarbonising the UK steel industry. It favours going down the primary steelmaking route using directly reduced iron (DRI) technology citing its role in building nuclear submarines and wind turbines

The trade union Unite said that around 1,500 Tata Steel workers will begin an indefinite strike from July 8 (four days after the general election) over Tata’s plans including cutting up to 2,800 jobs. Tata has now responded by threatening to advance the shutdown of its blast furnaces saying strike action would put the safety and stability of its operations at risk.

The contrast with Tata’s plans elsewhere in Europe

Tata’s other largescale steel plant in Europe is the 7 million tonnes/year capacity plant at Ijmuiden in the Netherlands. The company’s Green Steel Plan seeks to transition to primary steelmaking via the DRI and EAF route in two phases, the first to be completed by 2030. Tata Steel Netherland has already awarded engineering contracts to Danieli and Tenova for a gas-based DRI plant an EAF and other facilities. This could be switched to run off green hydrogen in the future. Tata has now said that it is in detailed talks with the Dutch government. They have proposed a decarbonisation roadmap amid reports that the government may provide as much as three billion euros to the project. Unlike in the UK, Tata has completed a renovation and relining of its blast furnace number 6 at Ijmuiden which will only be decommissioned in 2035 when the transition to low carbon technology is complete.

What are other UK steelmakers doing?

There are two other crude steel producers in the UK, British Steel and Liberty Steel.

Financially struggling Chinese-owned British Steel plans to replace the two blast furnaces at its Teesside and Scunthorpe sites with scrap-based EAFs. Latest reports suggest the company is asking for 600 million pounds of taxpayer support to make the transition. This is likely to be controversial given that China produces over half of global crude steel output. China is also is regularly accused of dumping steel into overseas markets.

Liberty Steel, owned by commodities tycoon Sanjeev Gupta, has said it will restructure its UK steel business after a deal with creditors in late March. The company plans to double its scrap-based electric arc furnace capacity at its Rotherham plant to two million tonnes/year.

An overall perspective on the UK steel market

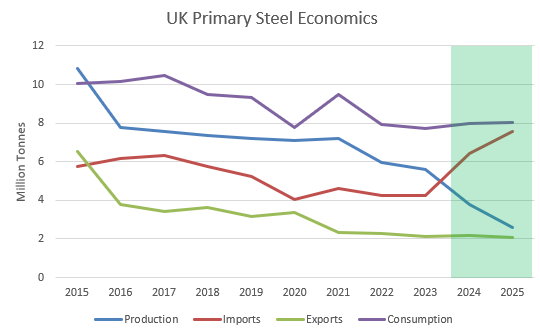

The closure of Tata’s blast furnaces is expected to produce a large jump in UK steel import dependency.

BREXIT – The elephant in the room

Brexit has left the UK steel industry outside the European single market adding to trading difficulties. Tata finds itself on both camps and, so far, has opted to invest more in its Dutch operations with has ready access to markets in 26 other member countries. Further problems are likely to emerge from the EU’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The initial phase of CBAM came into force in October 2023 with simplified monitoring and reporting. The full impact starts in 2026 offering tariff protection to green steel projects in member countries.

Could scrap-based steel production work for the UK?

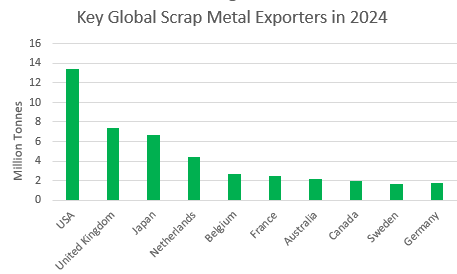

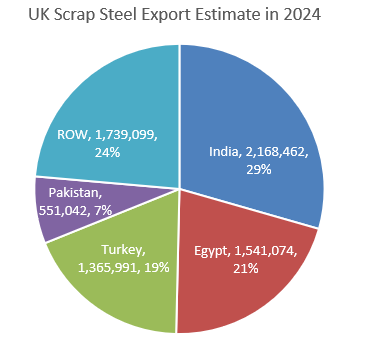

The simple answer is yes, as the UK is the world’s second largest exporter of ferrous scrap after the USA.

A major shift to scrap-based EAF production would pose problems for some UK scrap customers, particularly as other leading exporters are looking to boost domestic scrap usage.

How will all this play out?

Much will depend on the attitude of Tata and whether a possible incoming Labour government can persuade it to change direction by boosting available subsidies. Tata says it is losing one million pounds a day from steelmaking in the UK. The stakes are high with the possibility of a severe contraction in the industry unless new deals can be reached.