Decarbonization has shot up the global priority list, even with the advent of Coronavirus. Environmental conscientiousness has grown to be at the forefront of today’s minds and businesses. Despite LNG being the cleanest fossil fuel available, policies surrounding the role of carbon bridge fuels are frequently under debate.

The Debate

In this decarbonization process, LNG is considered as a “bridge”; an intermediary fuel which is responsible for lower emissions, at least upon first glance. As a result, huge investments have been made in LNG in recent years.

Many are now questioning whether LNG has a place in an ideal ‘decarbonized world’. Global leaders, like Joe Biden and Bill Gates, have recently expressed views that we need to work harder to meet the 2050 objectives. This would mean accelerated phasing out of fossil fuels – gas included.

In contrast, oil majors believe increasing LNG trade in the short term would be a quick win. This means lower environmental impact whilst shifting operations to more sustainable solutions. A gas fired power plant emits half the amount of carbon compared to a coal-fired one. As most of the emissions come from power plants, they are, in theory, easier to capture and store underground. LNG can also be used to generate hydrogen, perhaps a solution for powering some of the maritime fleet.

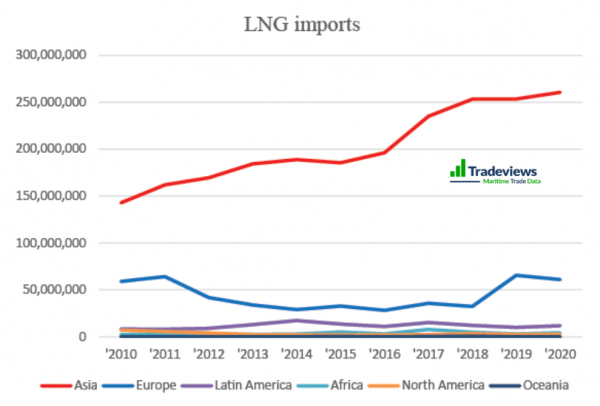

Asia Holds The Reins

Asia was the major importer of LNG in 2020. It commands a large market share, which according to Tradeviews is 77%. This is partly explained by the impressive growth trajectory for many Asian countries. Japan, China, India and South Korea are the largest importers. Even if Europe and America encouraged limiting LNG trade, Asia, in particular China, has the power to influence this market. China’s demand for LNG imports seems to be doubling every 5 years. China is currently the second largest importer of LNG in the world, at 65 million tonnes in 2020, just behind Japan.

Along with China, India has adopted an incremental growth of LNG, based on supportive government policies and improved pipeline infrastructure. In contrast, Japan and South Korea rely more on nuclear energy, coal and renewables which will probably cause LNG imports to shrink in the future.

Supply Side

Sources for the supply of LNG are fairly widespread geographically: The Middle East being the major exporter. Qatar was the second biggest trader in 2020, after Australia. A drive of LNG from the Middle East was expected considering they are leading in oil production. Other significant exporters are Russia and North America. Within four years, 2017-2021, North America increased exports by five times as much, reaching almost 50 million tonnes in 2020.

Other Headwinds

Coronavirus hasn’t helped LNG development projects, only adding further delays.

Recently ‘Total’ announced they indefinitely suspended it’s Mozambique liquefaction project. The project was initially due to be completed in 2023 but was declared a force majeure after attacks from Jihadists. It is believed the project would involve 16 new LNG carriers worth around $2.9 billion. However recently, ‘Total’ said they would continue the project in one years’ time, pushing the completion date to 2025.

Future Expectations

LNG as a cargo has a longer life than its carbon counter-parts. Coal has probably already peaked and perhaps oil has too, after the Covid Crisis altered global demand. The longevity of LNG is still unknown.

While LNG will continue to grow for now, the big question is ‘when can we expect it to peak?’ Until 2040, growth is visible when looking at stated policies. If we are going to meet the limits for the rise in global temperatures to 1.65 degree C, LNG’s peak will need to happen a lot earlier: perhaps by 2025. There is still a way to go for the role of carbon bridge fuels.